And now back to the depressing cold winter weather outside -- which is best spent in a museum (or listening to an interesting talk).

To Oxford ....

I am a student at the University of Toronto (Canada), going on what was once called "the Grand Tour" -- a trip around the whole of Northern Europe (and, perhaps, in the near future, Southern Europe as well). My parents and I should be spending about 3 months on our tour. I hope you will enjoy reading about my experiences, and feel free to suggest places to go (or pictures to take).

And now back to the depressing cold winter weather outside -- which is best spent in a museum (or listening to an interesting talk).

I don't think they sell Chiclets (a kind of chewing gum) in Canada, but if any of you have been to Asia, you'll recognize the name.

Most of you probably have sat on rattan chairs -- they're the kind which look like the have been made of strips of wood (which you probably thought was some kind of bamboo).

By its name, Titan Arum, you know that the tree has something gigantic (or titanic) in size.

An English Robin.

This one is really young. Cork oaks can grow for about 200 years, producing cork for about 150 of those years.

This is cork -- the actual tree bark from which corks are made.

Another interesting plant -- the so called "Century Plant".

Some unusual cacti. (also in the dry desert ecosystem).

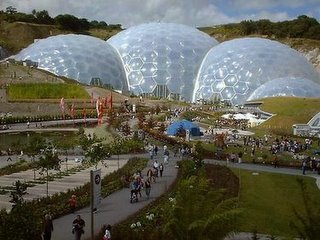

Unlike the Biosphere, the Eden project contains only two different biogeographies, indoors.

This was the best picture I could get of this quick bird -- in the early morning light, it was almost impossible to get a good image.

There were lots of birds at Stonehenge -- especially when my mum and I started feeding them (indeed, they were so unafraid of us, one of them would even eat from our hand).

Another part of Stonehenge, which is not commonly known about is the chalk avenue leading towards the circle.

Stonehenge, as you might know, was built in series.

I don't think you really appreciate the age of stonehenge until you see the lichen on it.